At the Met, All That Dazzles Is Not Just Gold — It’s Feathers, Too

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas

With its cheerfully crowd-seeking title, “Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas,” … the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition of pre-Columbian art promises an unabashed celebration of splendor. Offering more than 300 objects spanning nearly 2,500 years, and representing cultures from the Moche, Wari and Inca to the Olmec, Maya and Aztec, it delivers in full. Riches abound.

Вернуться на Главную

But this fascinating show also puts to rest some popular misconceptions. While the conquistadors of the 16th century plundered Central and South American kingdoms for wealth, more recent outsiders have tended to endow the empires with false simplicity. Figurative stone carvings from Mesoamerica — several are included here — have been celebrated by modern artists for their bold stylization rather than their nuance. Indigenous handicraft traditions popularized for tourism and export have emphasized a legacy of homespun goods.

Pointing to a very different aspect of these civilizations’ heritage, the adornments, utensils and textiles gathered here, most made with precious materials, all demonstrate dazzling sophistication.

Among standouts in the first gallery is an “Octopus Frontlet” (A.D. 300-600) made by the Peruvian Moche. With its catfish-headed tentacles surrounding a wild-eyed, shell-toothed face, it introduces the bounty of gold body ornaments in the exhibition, which traces the northward spread of metal working from present-day Chile to Peru, Colombia, Central America and Mexico.

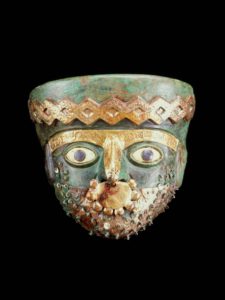

Full of invention and animation, and often spangled with little bells and other bits of flickering gold, these adornments were crafted exclusively for rulers. Notable early on are “earflares” big as bangles; the oldest here, found in Peru, date to 800-500 B.C. They were meant to be worn in enlarged earlobe piercings. Evoking the coronas of blazing suns, the earflares would flank faces further graced with towering gold diadems and, most unfamiliarly, substantial nose ornaments. These fire-breathing curtains of figured gold hung from the septum, generally covering not only the upper lip but also, conspicuously, the mouth. The various Andean civilizations, ultimately consolidated into the sprawling Incan empire, had no written language; it seems their rulers were people of few spoken words, as well. Three funerary masks, all with lidless, glowering eyes, suggest the immensity of power they invested in a silent stare.

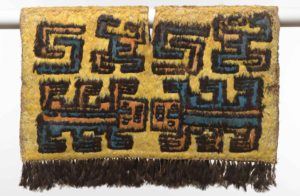

Despite its allure, gold was not the most prized material in pre-Columbian cultures. For the earliest, which date to the second millennium B.C., that status was held by woven and embroidered textiles, which take longer to make. Surpassing value was also placed on the pinkish shells of spondylus, a species of spiny oyster. Feather workers were more esteemed than gold workers — and indeed they produced wonders, as in a series of shockingly vibrant panels made with tens of thousands of blue and gold macaw feathers by the Wari of Peru in A.D. 600-900, their function unknown. In Mesoamerica jade was favored. And in whatever material, all the luxury items on display were “efficacious,” says the exhibition’s co-curator, Joanne Pillsbury. (Now at the Met, Ms. Pillsbury led this show’s considerable curatorial and research team while she was at the Getty Museum, where “Golden Kingdoms” originated.) That is to say, these luxuries were believed to be animated by gods, and to consolidate — and radiate — power.

A tabard with lizardlike creatures and feathers on cotton from A.D. 500–750 Peru.CreditKatherine Wetzel/Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Burial mask made of copper, gilded copper, shell and stone from A.D. 525-550 Peru.CreditMuseo de Sitio de Chan Chan, Huanchaco, Peru

As is particularly evident in woven and embroidered textiles, the Andeans’ visual language was elaborately encrypted and even the most highly abstracted geometric patterns harbor figuration. Witness a striking Wari woven tunic which, a label informs us, contains abstracted faces.

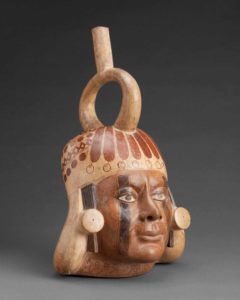

A big gold helmet from Panama (A.D. 700-900) is decorated with “three double-headed crocodilians with anthropomorphic bodies”; unaided, it seems a baffling, if mesmerizing, psychedelic maze. One wonders whether this inscrutability is another expression of divine might, especially as some more prosaic objects — a Moche painted ceramic “portrait vessel” of a warrior known as Black Stripe for his facial markings, for instance — are marvels of realism.

A painted ceramic “portrait vessel” from A.D. 400-650 Peru. The depicted warrior was known as Black Stripe for his facial markings.CreditMuseo Larco, Lima, Peru

Faced with glorious objects made in the service of power, we are obliged to measure pleasure against cruelty. As is shown by the painted narrative a Moche ceramic vessel and also by a pair of Inca votive figures, human sacrifice, including of children, was in some places a ritual practice. So was the use of psychoactive substances; a few spoons likely made for inhaling them are on view. One, crafted of gold and silver by the Chavin of Peru in 400-200 B.C., is topped with a crouching figure; on the underside of the stool on which he sits is a face that would watch the user as he lifted it toward his nose.

Of course art, religion and extreme experience have consorted since the beginning of time, and continue to do so in the sculptures produced in what is now Mexico, where it is something of a relief to see figures in full interacting actively and expressively. The drive to communicate is evident in the Mayan development of a pictographic language, as in a richly colored codex of 1350 A.D., inscribed on deerskin — a rare treasure.

A tabard and necklace made of a variety of shells from A.D. 900-1200 Mexico.CreditMuseo Nacional de Antropología, Secretaría de Cultura-INAH, Mexico City

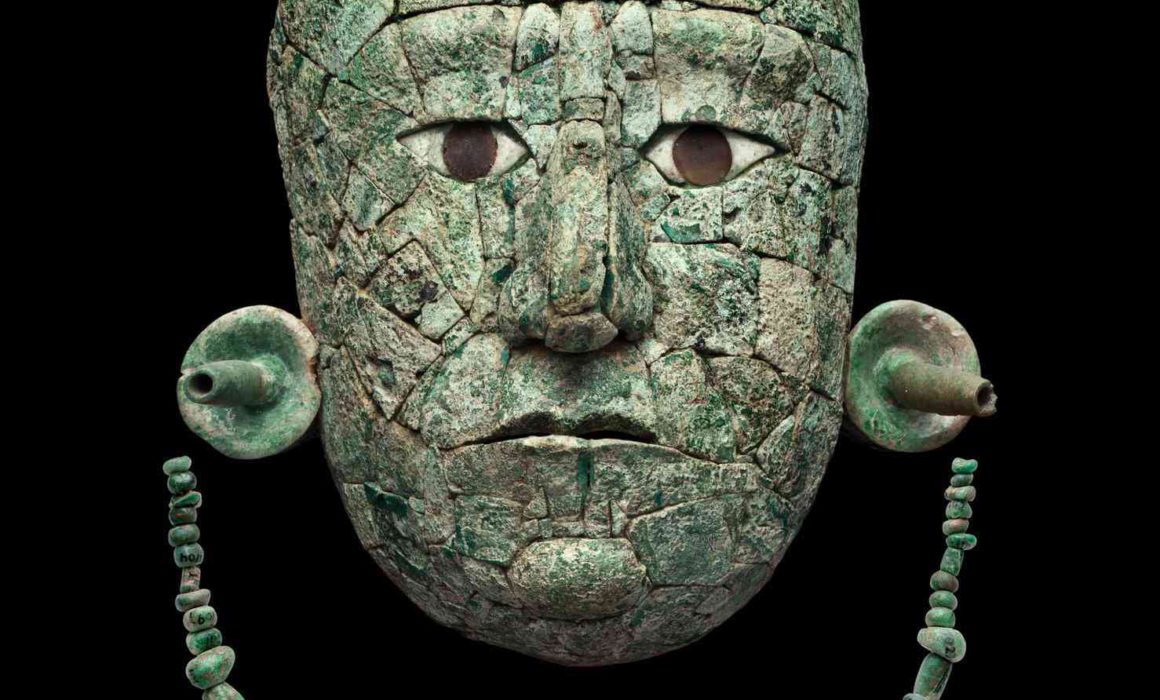

But these Mesoamerican cultures, which judged jade far more valuable than gold, are rightly known for their stone carvers. A wonderfully vivid and graceful Mayan relief from 736 A.D. depicts a bejeweled King Pakal I seated cross-legged; leaning to his right, he hands a stingray-spine blood-letter to his grandson, while two masked courtiers look on. Pakal’s wife, the so-called Red Queen, is represented by a mask of jadeite and other stones, her face an emblem of serene command. From the same period comes a grand limestone stela of another Mayan queen, who wears a soaring feathered headdress and a full complement of jewels, along with a skirt of jade beads. The presence of female rulers in this exhibition reflects new scholarship; recent excavations reveal that women as well as men of the South American cultures wore facial ornaments and were honored with elaborate burials.

“Golden Kingdoms” is entered through the Met’s Greek and Roman galleries, encouraging comparisons that do not necessarily favor the ancient Mediterranean world. The “fine line” painted ceramic bowls of the Andes are as fluently narrative as red-figure Greek pots.

A mask of the wife of King Pakal I, the so-called Red Queen, in jadeite and other stones from A.D. 672 Mexico. Mesoamerican cultures judged jade far more valuable than gold.CreditMuseo de Sitio de Palenque

Lessons in cross-cultural affinities become explicit in the exhibition’s final rooms, where there is an exquisitely inlaid turquoise and mother-of-pearl mask that found its way to the Renaissance duke Cosimo de Medici. A sleepy little panel picture of St. Gregory, made soon after the Spaniards arrived, turns out on close inspection to be rendered, rather miraculously, in tiny feathers. More attention grabbing is a big painted portrait of Don Francisco de Arobe and his two sons, from 1599. Himself the son of a former slave of African descent, Francisco was a chieftain of the Esmeraldas, in what is now Ecuador. His portrait was commissioned by the King of Spain to commemorate Francisco’s allegiance with the Crown. All three of the painting’s subjects wear seashell necklaces and European ruffs, gold nose ornaments and tunics of Asian silk. Each clasps an iron spear bespeaking an African warrior.

Nothing about the 21st century’s…