Why There Will Be No Trade War Between The U.S. And China

China accounts for nearly half (43.6%) of America’s total trade deficit with the entire world.

The big guns are in Beijing. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, Director of the National Economic Council Larry Kudlow, and … Director of the National Trade Council Peter Navarro are all visiting China to talk trade. That’s just about the entirety of Trump’s economic team.

Вернуться на Главную

The expert consensus is that they won’t achieve much. They say that the team is too big and too diverse. But the experts have often been proven wrong when it comes to the U.S.-China relationship in the age of Xi and Trump. Politics as usual have gone out the window in both countries. Xi and Trump are unconventional leaders who are willing to push the limits to get what they want.

Yet for all their public bluster—Trump via his personal Twitter account, Xi at secondhand via the jingoistic Global Times party tabloid—the two leaders have shown a remarkable ability to work together. Xi Jinping is almost certainly behind the sudden progress toward peace on the Korean peninsula. And Donald Trump has quietly droppedAmerican objections to China’s human rights record.

Common goals

Just as on other issues, behind the scenes Trump and Xi seem to be working together on trade. At first glance, that may sound ludicrous. China’s trade surplus with the United States hit a record high in 2017, and is on track to repeat this year. But China has actually been working hard to bring down the politically-sensitive surplus, and though it may seem somewhat out of character, Trump has quietly recognized that fact.

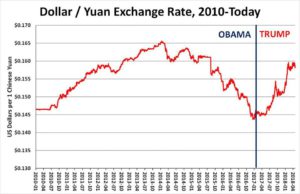

Economic theory holds that trade surpluses are a sign of an undervalued currency. As a candidate for President, Trump campaigned relentlessly against China’s currency policies, and even promised to label China a currency manipulator on Day 1 of his Presidency. That day came and went with no announcement and since his inauguration, Trump has turned down the opportunity to do so several times. The reason? It’s probably no coincidence that the Chinese yuan has risen 8.6% against the dollar since Trump took office.

The dollar/yuan exchange rate expressed as U.S. dollars per 1 Chinese yuan, January 2010 — April 2018. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

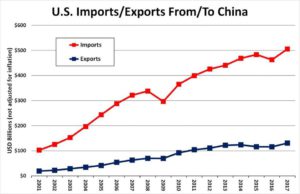

The rising yuan (falling dollar) has, in fact, spurred higher U.S. exports to China. American exports to China hit an all-time high of $130 billion in 2017, up $15 billion from 2016. Prior to Trump’s inauguration, American exports to China had been on a declining trend since 2014. The bounce back is almost certainly due to the weaker dollar, which allows American exporters to undercut competitors in the European Union. A strong Euro (up 13.9% against the dollar) has also helped.The problem (for Trump) is that U.S. imports from China have increased even more, from $463 billion in 2016 to $506 billion in 2017. As a result, the trade deficit has widened from $347 billion in 2016 to an all-time high of $375 billion in 2017. That means that China accounts for nearly half (43.6%) of America’s total trade deficit with the entire world.

U.S. imports from and exports to China, current USD billions (not adjusted for inflation). Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census

Of course, China represents around 20% of the global economy outside the United States, so perhaps its outsized share of the U.S. trade deficit is not so surprising. And the true trade deficit in value-added terms is probably closer to $200 billion, since much of the value in China’s exports to the United States consists of components that are actually made in other countries. And the U.S. has a massive $32 billion trade surplus with Hong Kong, which is after all part of China. On top of all that, the U.S. actually has a $38 billion surplus in trade in services with China. Still, hedge all you want, the deficit is enormous—and enormously political.

Politics is local

National trade deficits make for good soundbites, but they don’t really swing votes. China’s surging imports dominate the national headlines, but ultimately it’s U.S. exports that drive the local political battles that are at the heart of American electoral politics. A weaker dollar (and a stronger yuan) benefits U.S. exports. But instead of driving down U.S. imports, the weak dollar may just make them more expensive, pushing the deficit even higher.

The things that the U.S. exports to China are in competition with the rest of the world: American soybeans and aircraft, for example, compete with producers in South America and Western Europe. A weaker dollar makes these American products cheaper than those of their international competitors. Big exporters like Cargill and Boeing benefit tremendously from a weaker dollar.

This photo taken on April 9, 2018 shows workers transferring soybeans at a port in Nantong in China’s eastern Jiangsu province. President Xi Jinping vowed on April 10 to take new steps to open China’s economy ‘wider and wider’ amid a broiling trade confrontation with the United States. (AFP/Getty Images)

But America’s main imports from China—the phones and gadgets that go under official classifications like «electrical machinery» ($129 billion) and «machinery» ($97 billion)—are often produced only in China. It has been suggested that the iPhone 7 alone may account for 4.4% of the U.S. trade deficit with China. A stronger yuan just makes these imports more expensive in dollar terms. No matter how strong the yuan is, they’re still going to come from China.

Action on access

Yet amidst all the trade war rhetoric, China has been careful to target American products like soybeans that can easily be diverted to other markets. China’s threatened aircraft tariffs seem specifically designed not to hit Boeing. Meanwhile the Trump administration’s proposed tariffs on Chinese good focus on the few specific sectors where Chinese imports compete directly with American products.

Mnuchin & Co. are likely to belay U.S. tariffs in exchange for Chinese action on market access. China’s push to prop up the yuan has already had the same effect as an 8% across-the-board tariff on Chinese goods entering the United States, to no avail. But the real story in the U.S.-China economic relationship isn’t Chinese exports. Many of those (like Apple) are «American» anyway. It’s Chinese imports.

Each of the U.S. negotiators in Beijing likely has a list of the products he would like to see China buying more of, and each of them is likely to get commitments on at least some of the products on his list. Whatever the ultimate number, it will be enough to go home and declare victory. In return, the U.S. will continue to be China’s best customer.

After all, the 2018 trade deficit figures won’t come out until …