Narcissism. Know thy selfie

It is time to stop invoking narcissism in the diagnosis of so many modern ills. Self-love has its virtues

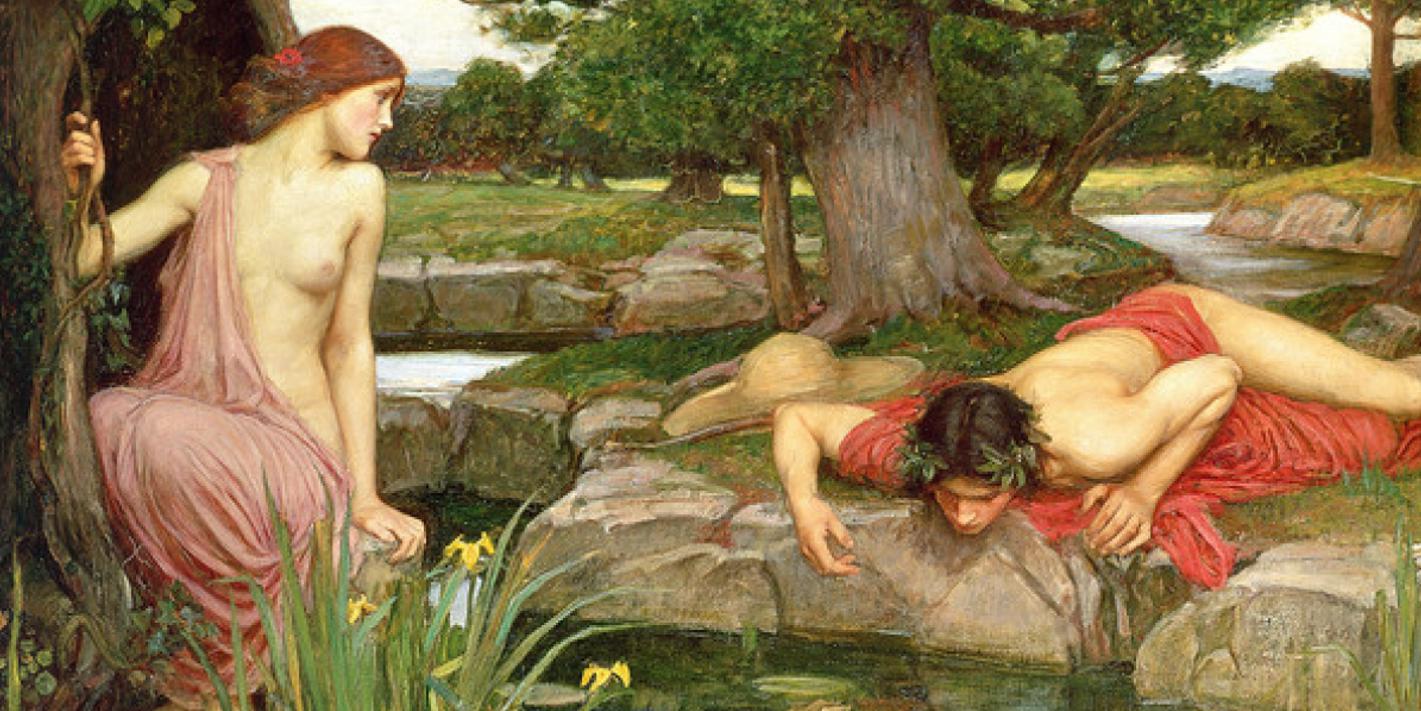

WAS Narcissus a narcissist? Arguably not … Consider the difference between the famously beautiful boy, who spurned the advances of others, and another unfortunate character from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses”. Actaeon, a keen hunter, instantly realised that he had been turned into a stag when he saw his head and antlers “mirrored in a stream”. Yet when Narcissus fell in love with a reflection, a few lines later in Ovid’s poem, he did not recognise himself. Indeed, he recoiled in horror as soon as it dawned on him that it was his own face that he had been admiring in a pool. Narcissus was, one might say, enraptured not by a “selfie”, but by what he took to be a non-selfie. The poor boy, notorious for alleged self-absorption, may have been unfairly judged for the past 2,000 years — though he was certainly guilty of pride.

Вернуться на Главную

In 2013 Oxford Dictionaries anointed “selfie” its word of the year, to mark the exploding popularity of this novel term for a self-portrait, usually one taken by a smartphone and posted on a social network. As the blurbs for two new books note, the rise of this form of self-promotion has been widely taken as evidence of a boom in self-regard or selfishness. If there is such a boom, it is presumably a repeat outbreak of the epidemic of narcissism diagnosed by critics in the 1970s—“the Me-Decade”, as Tom Wolfe, an American journalist, dubbed it.

In “The Americanization of Narcissism”, Elizabeth Lunbeck, a historian at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, explains how narcissism came to be “the pundits’ favourite diagnosis”. By 1979, when an influential historian, Christopher Lasch, published “The Culture of Narcissism”, many American intellectuals spoke the language of psychoanalysis as if it were their mother tongue. There was a receptive audience for the Freudian idea that repressed self-hatred could lead to self-absorption, grandiosity and shallowness in individuals, and for the notion that this personality disorder could somehow be reflected in the spirit of a wealthy, coddled and self-indulgent age.

For Sigmund Freud, there was a good sort of narcissism, at least in early life, and a bad sort. Narcissistic drives—urges aimed at nurturing the self—were a component of healthy development. But they could go awry, resulting in excessive self-love of various sorts, and you were supposed to grow out of them. Sometimes the Freudian picture got rather convoluted. Male homosexuals, Freud suggested in 1910, looked for partners modelled on themselves, because an exaggerated erotic attachment to their mothers made them want to love others in the same way that their mothers had loved them.

As Ms Lunbeck notes, the good aspects of self-love were neglected by Freud and by his most influential followers, who started to see bad narcissism everywhere. In the 1930s some analysts tried to get a better press for a “healthy” adult narcissism which, they argued, underpinned a well-adjusted life. But their voices were drowned out by other analysts, and by the jeremiads of social critics who were eager to find a pseudo-scientific framework for their attacks on consumer culture.

In “Mirror, Mirror: The Uses and Abuses of Self-Love”, Simon Blackburn, an emeritus professor of philosophy at Cambridge University, and one of the best popularisers of his discipline, comes at narcissism from a different angle. He examines it through philosophical debate on ethics, integrity, hubris, self-respect and temptation, among other things, and through the lens of literature. He does not spend much time on the speculations of professional psychologists. But, like Ms Lunbeck, he too suggests that self-love is not always as bad as it has been painted. A sense of self is a precious thing, he argues, and he reminds us what a disaster it is to lose it—to dementia, for example. Although self-consciousness can be debilitatingly intense, as in adolescence, the lack of it has its perils too, not just for propriety but for morality.

Finding the right value to put on oneself is a balancing act, Mr Blackburn sagely observes, though there are no simple rules that can steer us between the Scylla of excessive self-love and the Charybdis of its opposite. The matter of “positioning oneself among others in the social world” is a complex one, so discovering the right mix of attitudes and feelings “may be like finding the centre of gravity of a cloud”.

Sometimes, he writes, it is plain that the balance between self-interest and a proper concern for others has been seriously upset. For him, a clear example of this is “the ‘greed is good’ culture that spread across banks and boardrooms in the last thirty years”. Few will disagree when Mr Blackburn says there has been no recent shortage of financial egotism, though the inclusion of Rupert Murdoch in his gallery of financial villains suggests a certain nebulousness in his conception of it.

In a tongue-in-cheek prefatory acknowledgment to L’Oréal, a cosmetics firm, Mr Blackburn reveals that …