Sochi or bust

The conspicuous dazzle of the games masks a country, and a president, in deepening trouble

FEBRUARY 7th sees the opening of the winter Olympics in … Sochi on the Black Sea. The message of the games is simple: “Russia is back”. Sochi was planned as a celebration of Russia’s resurgence, a symbol of international recognition and a crowning moment for Vladimir Putin, its president, who for the present seems to have seen off all his challengers.

Вернуться на Главную

Appropriately, the opening ceremony will include the image of the Russian “troika-bird” from Nikolai Gogol’s “Dead Souls”. “Rus,” wrote Gogol, “aren’t you soaring like a spry troika that can’t be overtaken? The road is smoking under you, the bridges thunder, everything steps aside and is left behind!…Is this lightning thrown down from heaven? Other nations and states gaze askance, step off the road and give [you] right of way.”

The quote has long been used to justify Russian exceptionalism and moral superiority. Gogol describes Russia as a deeply flawed and corrupt country, but it is precisely its misery and sinfulness that entitles it to mystical regeneration. His troika carries a swindler, Chichikov, and his drunken coachman, but it is transformed into the symbol of a God-inspired country that gloriously surpasses all others.

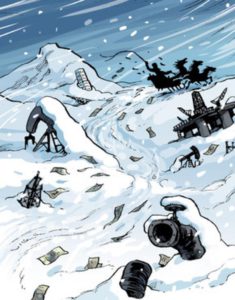

So, too, with the Sochi Olympics. This grand enterprise, the largest construction project in Russia’s post-Soviet history, is also a microcosm of Russian corruption, inefficiencies, excesses of wealth and disregard for ordinary citizens. The Olympics are widely seen as an extravagant caprice of Russia’s rulers, especially its flamboyantly macho president, rather than a common national effort. The cost of the games has more than quadrupled since 2007, making them, at $50 billion, the most expensive in history. One member of the International Olympic Committee thinks about a third of that money has been stolen. Russia’s opposition leaders say the figure is much higher.

Sochi also illustrates Russia’s continuing troubles in the north Caucasus. After the twin suicide-bombings in Volgograd, 430 miles (690km) north, at the end of December, Sochi, a resort town of 400,000 people, has been turned into a fortress guarded by around 100,000 security and military personnel. Missiles bristle in the mountains, high-speed boats and submarines patrol the coast, and drones watch from the sky. Russia’s 58th army, last employed in a war against Georgia in 2008, will secure the southern border. Instead of opening up the country to tourists, these games are likely to be remembered as the most closed in history. Russia’s security agencies are issuing special passports to all spectators to filter out not only potential terrorists, but also political troublemakers.

The tight security is reminiscent of the 1980 Moscow Olympics, when non-Muscovites were barred from the capital and undesirables shipped out. These are not the only parallels. Both games are marked by hostility between Russia and the West. In 1980 several countries, including America and West Germany, boycotted the games in protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. This time the teams will attend, but their leaders, including President Barack Obama, will stay away.

The picture has already been overshadowed by violent clashes in Ukraine, the result of a bitter geopolitical contest between Russia and the EU. Ukraine is essential to Mr Putin’s ambitions of creating Russia’s own Eurasian Union, a diminished version of the Soviet Union that was. The Kremlin may not be projecting its power with military force, but it is trying to draw Ukraine into Russia’s orbit with money, gas and counter-intelligence, while warning the West not to meddle. It is hardly the behaviour of an amiable Olympic host.

Soviet ghosts

Perhaps the most striking parallel with the earlier Olympics is the state of the economy. At one level, to be sure, Russia looks completely different. The government no longer regulates prices; there is a large private sector. Russia no longer wastes time and money producing things nobody wants. The military-industrial complex, which once guzzled national resources, has shrunk. Middle-class Russians dress, shop, eat and travel much as their peers do in the West. Consumption is conspicuous. Yet a closer look reveals that the country is almost as vulnerable as it was in 1980.

That year was the peak of Soviet economic stability. Oil prices were high, and the Soviet Union was increasing its exports of energy through a new pipeline to the West. The proceeds from those sales paid for the vast state and financed the import of grain and clothes. While the West was going through a crisis, the Soviet Union was enjoying modest economic growth. A few years later, however, oil prices fell and the regime began to crumble.

In today’s Russia, oil and gas account for 75% of all exports, compared with 67% in 1980. Although Russia no longer buys grain from America, as it did in the 1980s, 45% of what Russians buy today is imported. Walk around a department store in central Moscow, and it is hard to find anything that is produced locally. The state remains the single largest employer, while its corporations — controlling natural resources, infrastructure, banking and media — dominate the economy.

As Clifford Gaddy and Barry Ickes, two American economists, have argued, the highly inefficient industrial structure of the old Soviet economy, based on misallocation of both resources and people, remains intact. The oil rent reinforced and perpetuated it: it has bought political stability and the loyalty of the population, but has slowed down modernisation. Inevitably, the result is stagnation.

Money as alcohol

Last year, just as the developed world began to recover from recession, Russian economic growth slowed to under 1.5%. Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development says the economy is not about to return to high growth, and even Mr Putin was forced to admit in December that the main reasons for the slowdown are internal. The era of high growth, which coincided with Mr Putin’s first period of rule, is over.

Two main factors drove growth then, neither of which had much to do with him. The first was the collapse of the Soviet economy; the second was the market reforms of the previous decade, which freed private enterprise. As Yegor Gaidar, the architect of those reforms, pointed out, the growth that began in 1999 — the year Mr Putin came to power — was largely the result of recovery, and was observed across the former Soviet Union. It required little new investment, and used up spare capacity left over from Soviet times. Then in 2004, as Mr Putin entered his second presidential term, oil prices began to climb sharply, cheap money flooded the country and consumption exploded. But instead of creating institutions and laying a foundation for future growth, the Kremlin used the oil revenue to consolidate power, suppress competition and reassert Russia’s influence in the world.

Although some of that money was stashed away in a reserve fund, a lot of it seeped into the real economy through budget spending, which fuelled consumption. In 2005 the Russian government balanced its budget at an oil price of $20 a barrel. In 2013 it needed a price of $103 to balance it. As Andrei Kostin, head of VTB, one of the largest state banks, half-joked recently, “A healthy budget for me is one that injects large amounts of money — particularly in December — into the banking system, which then permeates warmly and pleasantly — like beer after a hangover — through the entire banking system.”

Disposable income grew twice as fast as the economy in the 2000s, and so did consumption. The increase in living standards was partly achieved at the cost of investment. Although investment in new factories and equipment increased from 15% of GDP in 2000 to the current 23%, it was well below the level of even Soviet investment in capital stock, not to mention China’s. And as Natalia Orlova of Alfa Bank notes, half of all new construction in the pre-recession years was of shopping centres, rather than the factories that could fill those shops with goods.

The oil price is still high, and there is no shortage of money in the economy. In fact, it is the excess of money and the lack of institutions that are the problem. Money has long been the main instrument of the Kremlin’s power and governance, buying the loyalty of both the elites and the general population. After the crisis in 2009, the government increased public spending by 40%. This pushed up prices and fuelled imports, but did little for the economy. The salaries of public-sector workers have improved, but not the quality of their services. Poor education and health care still top the list of complaints among Russians, particularly outside the big cities.

Kirill Rogov of the Gaidar Institute, an economics think-tank, says that by increasing spending in order to fuel consumption-led growth, the government has pushed the cost of labour from 40% to 50% of the country’s GDP — the same share as in developed countries. Yet productivity remains at less than half its level in the EU. In the past, Russia made up for its dismal investment climate and poor institutions with cheap labour, which allowed firms to make profits and invest. Now its economy is trapped between bad institutions and expensive labour, which makes private firms uncompetitive.

Russia has hit the same problem as the Soviet Union did: it cannot grow by expanding the labour force. Demography compounds the difficulty. The labour force grew until 2008, but a dip in the birth rate in the 1990s means that it is now shrinking. To grow further Russia needs investment, the reallocation of resources and better institutions, especially property rights. Yet all this would inevitably threaten the central motivation of Mr Putin and his circle: to preserve a paternalistic model where the state — and those who identify themselves with it — are the only source of money and power.

Friends and placemen

The state is one of the chief obstacles to Russia’s modernisation. During the 2000s the number of bureaucrats almost doubled. A quarter of the workforce is employed in the public sector. The total number of people who depend on the state is between 35% and 40%, says Boris Grozovsky, a Russian economic observer. This, he says, points to the share of the electorate that benefits from the status quo. At election time municipal workers are bused in to show support for Mr Putin. Meanwhile, the main purpose of Russia’s civil service is to shuffle papers around and extract administrative revenue from firms and private citizens. The bureaucrats have little interest in fostering competition that might cost them their jobs.

This is particularly true of the security services and prosecutors who have been among the main beneficiaries of Mr Putin’s rule. Alexander Bastrykin, a faithful chief investigator, recently told a Russian state newspaper that “privatisation is a threat that could finish off the Russian economy.” Suspicious of private business, the Kremlin has entrusted the economy to state corporations, often run by former security servicemen and its few friends. Whereas oligarchs in Boris Yeltsin’s time were private businessmen who influenced the running of the state, the Putin-era oligarchs are former KGB men who have used state power to grab private businesses.

Some analysts estimate that these state companies control about half of Russia’s economy. They are sheltered from competition, soak up resources and stoke inflation. State companies award contracts to nominally private companies owned by friends and relatives of their managers. The Sochi Olympics are a prime example: the biggest contracts were given to firms run by Mr Putin’s chums, including Arkady Rotenberg, his boyhood judo partner.

This sort of thing creates a system of perverse incentives, fosters cynicism and cronyism and discourages those who want to use their initiative and skills. One man has worked for two companies owned by Mr Putin’s friends. His latest employer is a firm owned by a close relative of a powerful government official. “My salary is higher than I would get in an independent firm, but my responsibility is much less. I add almost no value. Connections decide everything,” he says.

Although Russia still boasts some of the most entrepreneurial and hardy businessmen, who are determined to succeed and continue to invest, many burn out and leave. Economic activity in the country is waning, mergers and acquisitions are drying up and capital and brains are flowing out of the country. Evgeny Gavrilenkov, the chief economist at Sberbank, Russia’s largest state bank, says the problem is exacerbated by the central bank which, in order to stimulate growth, is injecting liquidity into the market while also trying to support the rouble. This allows banks and their clients to speculate in foreign exchange rather than invest. Yet the main reasons for the slowdown in investment are uncertainty about the future and the lack of proper legal title to property.

Third time, not so lucky

Buying the loyalty of different interest groups is easy when the pie is growing, but much harder when it is shrinking. Once incomes began to fall, Gaidar predicted, the regime would face a choice between repression, which would eventually lead to revolution, and democratisation, which might also mean the loss of power. Mr Putin has tried to dodge that choice over the past year. He has made decisions ad hoc: staging show trials for political activists and locking up opposition leaders such as Alexei Navalny one day, then letting Mr Navalny run for mayor of Moscow the next. At the end of last year he released Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a tycoon he had kept in jail for ten years, but expelled him from the country. Spooked by the unrest in Ukraine, Russian prosecutors are demanding five- and six-year jail sentences for Russia’s own protesters. The independent TV Rain channel, popular with those protesters, is under fire.

As a faithful son of the KGB, Mr Putin would prefer to deal with the worsening economic situation as his one-time boss and political model, Yuri Andropov, did in the 1980s. Andropov suppressed dissidents while trying to modernise the economy from the top, thus keeping the regime secure. Mr Putin believes that if Andropov had not died in 1984, his plan would have worked. Yet he has also inherited a deep fear of unleashing the mass repressions and purges which Andropov’s generation of leaders agreed to abandon after Stalin’s death, in order to preserve themselves.

Skilful tactician though he is, Mr Putin does not seem to have a strategy. He may be hoping that the oil price will recover. At present it has stabilised at about $100 a barrel, but it is unlikely to stay there. With the rise of fracking in America and elsewhere, analysts estimate that the price could drop by 15% in the next six years.

Given the relatively low level of state debt, Russia could also start borrowing more to keep the budget afloat. This is what the Soviet Union did when the oil price fell. The Russian economy is far better equipped to deal with an oil-price drop than the Soviet economy was. It has built up substantial foreign-exchange reserves and has a floating exchange rate, which allows it to adjust to a fall. However, given the level of imports, a currency devaluation would hurt living standards and could lead to inflation higher than the present 6.7%. The unequal distribution of incomes in Russia means that, even if the economy continues to tread water, the bottom 40% of the population will see their economic situation worsen, says Mr Rogov.

Experts agree that, however the oil price moves, all scenarios “carry the risk of administrative crisis, elite squabbles and confrontation between the people and the regime”. Even with the oil price at its current level, attitudes to Mr Putin are changing fast, according to Mikhail Dmitriev of the Centre for Strategic Research — who has recently been removed from his post as the think-tank’s president. Over the past year discontent in the country at large has deepened and broadened, spreading across all social groups and ages. In contrast, Moscow and St Petersburg, where GDP per head is higher and infrastructure has improved, have become more stable and even loyal.

Mr Dmitriev says the latest focus groups show that Mr Putin is less associated with stability and more with uncertainty. His past achievements are becoming a distant memory, and his recent stunts, such as flying with cranes or diving for ancient amphorae, merely cause irritation. According to the Levada Centre, a pollster, almost 50% of the country does not want him to remain president after 2018 when his term expires. The change in mood has been caused not so much by worsening personal circumstances, as by a growing concern that the country is fast approaching a dead end. The danger for the world is that a weaker Mr Putin may be a more aggressive one, in Ukraine and elsewhere.

Mr Dmitriev says the latest focus groups show that Mr Putin is less associated with stability and more with uncertainty. His past achievements are becoming a distant memory, and his recent stunts, such as flying with cranes or diving for ancient amphorae, merely cause irritation. According to the Levada Centre, a pollster, almost 50% of the country does not want him to remain president after 2018 when his term expires. The change in mood has been caused not so much by worsening personal circumstances, as by a growing concern that the country is fast approaching a dead end. The danger for the world is that a weaker Mr Putin may be a more aggressive one, in Ukraine and elsewhere.

The risk for the Kremlin is not mass protests, but …