Mars exploration

Curiosity and Curioser

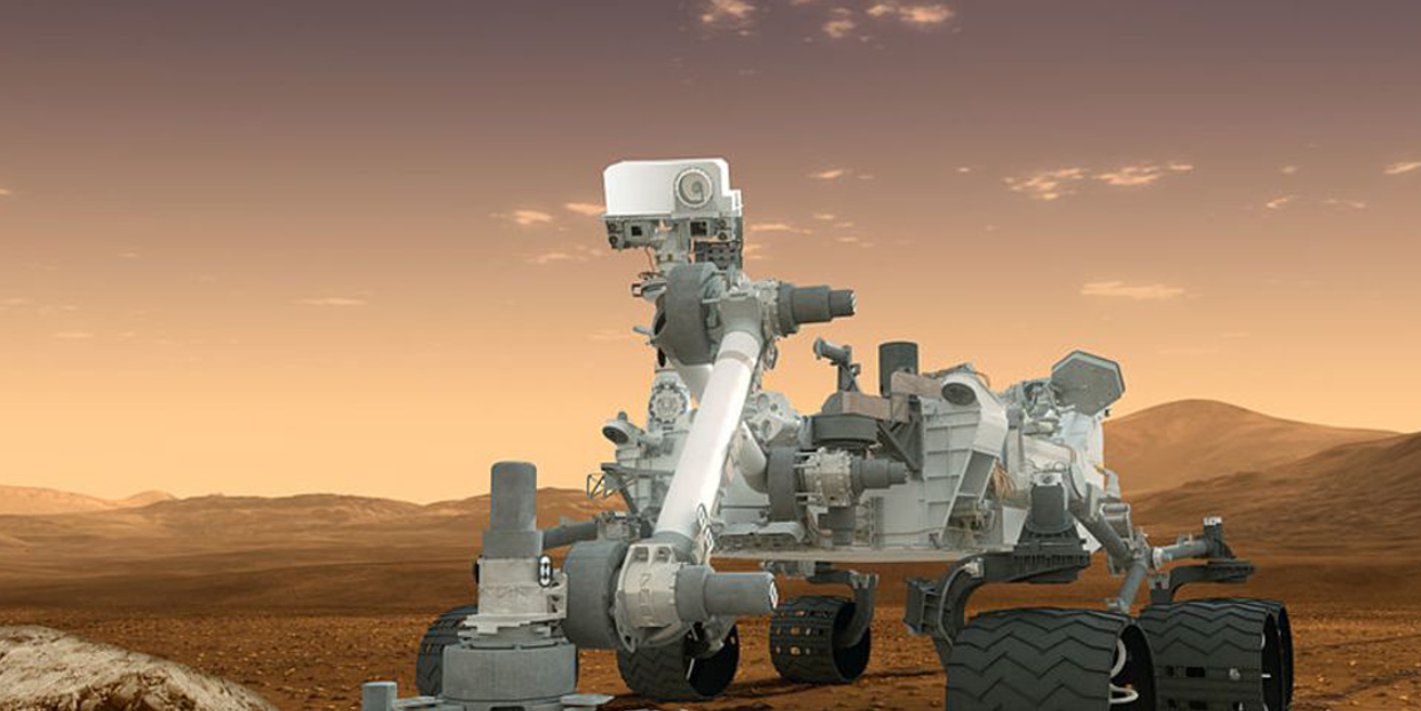

ATTENDEES at the American Geophysical Union’s autumn meeting in San Francisco were expecting to hear some big news about Mars. Sure enough, they got some — just not the sort they had anticipated. Until expectations were firmly damped down last week, they had thought they would hear about some sort of exciting discovery from Curiosity, the rover NASA landed on Mars this summer. In the event, the big — and, to some, not entirely welcome — announcement was that NASA plans to send Mars a second version of Curiosity to Mars in 2020, at a cost of about $1.5 billion.

Вернуться на Главную

With Washington headed towards a spending crunch, this seems like an odd time to be splashing out on another flashy planetary mission (one former NASA employee wondered whether the agency thought it could use the Heath Robinson-esque «skycrane» landing mechanism that delivered Curiosity to the surface to deal with the fall off the fiscal cliff). But John Grunsfeld, who heads up NASA’s science operations, was keen to stress that this mission would require no new money at all. In the budget it sent to Congress for 2013, the Obama administration sketched out its NASA plans for the rest of the decade, including how much it imagined spending on Mars exploration. Not all of that money was, at the time, allocated to specific missions. The new Mars rover, which will be built using spare parts from the Curiosity programme wherever possible, will soak up that cash.

This is an important point for Grunsfled to make, and not just to the keepers of the budget. Though Mars is a fascinating planet, it is not the only one that scientists are interested in. Those interested in Venus, say, or the moons of Jupiter, are keenly aware that no American spacecraft have been devoted to their destinations of choice since the 1980s. During that time NASA has landed on Mars five times and successfully put three more spacecraft into orbit round it, as well as losing a couple more through carelessness. A slew of new Mars missions are already in the works. Amidst such an embarrassment of riches, yet another Mars mission will cause disgruntlement, even if it is built within exisiting budgets. If new money turns out to be needed after all, that might turn into revolt.

Europeans, too, may feel put out by the decision. Until the president’s 2013 budget, NASA was meant to be supplying a fair bit of hardware — including rockets and one of those nifty skycranes — to Europe’s two «ExoMars» missions, scheduled for launch in 2016 and 2018. Earlier this year, pleading poverty, the Americans pulled out of the bulk of their commitments. Mr Grunsfeld insists that there is no contradiction in the fact that NASA now feels able to afford a new mission all of its own. The European missions, he says, required spending earlier on at a time when a couple of other American Mars missions will also be needing money, and that would have broken annual budgets. The new rover, launched later, allows the rate of spending to be kept even.

That last point, though, is telling. Keeping the spending going has a lot of political and institutional importance. JPL, the laboratory in Pasadena that runs most of NASA’s planetary missions, needs to have new thing to do if it is not to lay people off. The proposed rover fulfills that purpose admirably. So might missions to less regularly visited places — but as Mr Grunsfeld points out, many of the other places people are interested in, such as the moons of Jupiter, are very difficult to reach with large payloads, and trying to do so might end up costing a good bit more than $1.5 billion. As a way of keeping its premier planetary outfit (and the Californian legislators who take an interest in it) happy, a new Mars rover is a relatively risk-free proposition. There is a certain sadness in seeing an agency once charged by President Kennedy with mounting missions to the moon «not because they are easy, but because they are hard» doing things precisely because they are, by comparison, easy. But that’s politics.

…